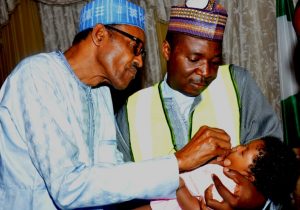

With the two year milestone since the most recent case of wild poliovirus in Nigeria approaching, the Expert Review Committee (ERC) on Polio Eradication and Routine Immunization has emphasised there is no place for complacency to keep the country polio-free.

Meeting in Abuja on 21 – 22 June, the ERC emphasised that the strategy in Nigeria must now shift: from interrupting transmission to staying polio free, sustaining the hard-won gains, strengthening routine immunization and responding to outbreaks of vaccine-derived polioviruses.

Important progress has been made in 2016 with nearly two years having passed since the last case of wild poliovirus was reported in Kano, and the type 2 component of the oral polio vaccine being removed from use in April, as part of a global vaccine switch. Yet the ERC emphasised the need to fill sub-national surveillance gaps, to make significant improvements to routine immunization and to address risks to the programme such as waning political commitment and accountability and the inaccessibility of some populations in the North-East.

Improving immunity and strengthening surveillance

The ERC assessed that recent supplementary immunization activities in Nigeria have been of good quality, with the number of children missed going down. This has been thanks to programmatic improvements such as activities in between campaigns at religious gatherings, and hit-and-run activities in inaccessible areas to rapidly protect vulnerable children. In newly accessible areas, innovations such as expanded age range campaigns are being considered to rapidly increase immunity in as much of the population as possible.

Overall, the ERC recognised that surveillance in Nigeria is strong, but with sub-national gaps that still need to be addressed. The ERC recommended determining how resources could be optimally used to fill these gaps. Both surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis and environmental surveillance have important roles to play in the coming years. Only once three years have passed in Nigeria with no case of wild poliovirus and strong surveillance systems can the WHO African Region be certified as polio-free, making the strengthening of s

Stopping all polioviruses

As well as keeping Nigeria free from wild polio, the ERC also recognised steps to stop vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPVs). In April, Nigeria successfully implemented the trivalent to bivalent oral polio vaccine switch, withdrawing the type 2 component of the oral polio vaccine alongside 155 other countries and territories worldwide within a two week period. In the long term, the switch will play an essential role in stopping the emergence of strains of type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreaks, which can emerge when routine immunization coverage is inadequate. The ERC also commended Nigeria for the successful campaigns that were carried out to make sure that immunity against type 2 was high at the time of the switch across the whole country.

Nigeria has seen one outbreak of circulating VDPV type 2 this year, in Borno state, in a sample taken from the environment on 23 March, before the switch took place. In response, the Director General of WHO approved the release of monovalent oral polio vaccine type 2 for up to three rounds to build immunity and stop the outbreak. The ERC congratulated Nigeria for their rapid response to this outbreak, with innovations and detailed micro-plans ensuring strong coverage and also recommended that Nigeria consider the possibility of using fractional dose inactivated polio vaccine for outbreak response strategies to further build up immunity against all types of poliovirus.

Strengthening Routine Immunization

The ERC was encouraged by the efforts of the Government of Nigeria and partners to improve routine immunization services. In particular, they noted the role of the polio eradication Emergency Operation Centers in improving logistics and tracking routine immunization coverage in 56 priority Local Government Areas. Yet with insecurity and insufficient coverage in some northern states, the ERC emphasised that investing in strengthening routine immunization through a comprehensive primary health care strategy must now be the priority of the government and partners in order to sustain the gains of the polio eradication programme and protect children against other vaccine-preventable diseases.

Transition Planning

The ERC also reviewed Nigeria’s progress towards planning for the ramp down of polio eradication funding in the coming years once eradication is achieved, and the potential to transition the polio assets and infrastructure to help meet other health needs. Nigeria is currently mapping the polio funded assets of both partners and the government, and is beginning to document lessons learned from the last few decades of polio eradication efforts in order to share their insights with other health programmes. The ERC recommended that the transition planning process align the redeployment of polio assets with the priorities and gaps of the primary health care system. A plan for transition should be completed by the end of 2016, driven by the government and with input from a broad range of polio and non-polio stakeholders, including donors.

Keeping Nigeria Polio Free

With progress made and challenges ahead, continued efforts in Nigeria are as crucial as ever in the light of two years with no wild poliovirus. With two remaining endemic countries – Pakistan and Afghanistan – no unimmunized child anywhere in the world is free from the threat of polio, especially where routine immunization is weak. Stakeholders of the polio eradication programme in Nigeria must continue full pelt until the continent has been certified free from the virus.