Micropatches provide potential new delivery method

An innovative new product may help the polio program to spare doses of IPV.

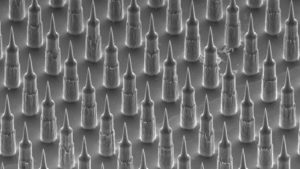

A new method of administering the inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) may be on the horizon, thanks to the collaboration of multiple Australian research centres and institutions. A Nanopatch is a vaccination tool consisting of an closely-packed array of microneedles which, when placed on the skin, can deliver vaccine into many thousands of cells in the dermis. The Nanopatch may one day enable unprecedented levels of antigen sparing. Just 1/40th of a full dose is sufficient for administration of IPV by micropatch.

As part of the upcoming switch from trivalent to bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), all countries are introducing at least one dose of IPV into their routine immunization systems. Fractional dose, intradermal IPV will be used in outbreak response for any circulating vaccine derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) following the switch, in conjunction with monovalent oral poliovirus vaccine type 2 (mOPV2).

However, IPV suffers from three key set-backs. Firstly, a globally constrained supply of IPV has meant that some countries have had to delay introduction until after the switch. Secondly, IPV is up to 15 times more expensive than OPV, which can be prohibitively expensive in some developing countries. Finally, IPV can only be administered by health-care professionals, using sterile equipment, making it more logistically difficult to operationalise during campaigns.

The recently published study investigated the immunogenicity of monovalent inactivated poliovirus vaccine type 2 (IPV2) administered by the Nanopatch. A fractional dose of IPV2 administered by Nanopatch elicited protective levels of poliovirus antibodies in 100% of animals. In contrast, animals receiving relatively large doses of IPV via intramuscular injection required 3 doses in order to achieve the same levels of antibody titres.

Through such a high level of antigen sparing, use of the Nanopatch could alleviate the global supply constraint of IPV, while simultaneously making the vaccine substantially less expensive per dose. The Nanopatch also benefits from ease of administration, and would be simple to use during campaigns or in outbreak response.

While optimism is warranted, there is still a substantial amount of work that need to be done before it can be taken further forward, not least clinical trials in humans, licensure in the country of manufacture and licensure in the country of use. However, this may be a vital new tool in our push to secure a lasting polio-free world, and prevent a child ever being paralysed again from this debilitating disease.