Innovation Series: The Last Millimetre

Research is delivering faster, cheaper and easier ways to administer the injectable inactivated polio vaccine to every last child

New ways of delivering the inactivated polio vaccine will help get vaccines the final millimetre of their journey to protect a child against polio. © Gavi

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative is finding new ways to administer vaccines to ensure that every last child is protected against polio. From new injection devices to injection-free modes of delivery, these innovations will be crucial in resolving some of the challenges of the next few years, both approaching eradication and beyond.

Since the 1950s, the world has been vaccinating children against polio, and as a result, numbers of children paralysed by the virus have fallen from 350,000 each year down to just 74 in 2015. The opportunity to eradicate a disease is not one encountered often in global health, and the rare chance that we face to end polio forever will bring many benefits. Not least on this list is the economic dividends; by removing the poliovirus from the face of the world for good, the world will reap savings upwards of US$50 billion, funds that can be used to address other pressing public health needs.

Good things come in small packages

Good things come in small packages

In the Polio Endgame, the injectable inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) will eventually be the only vaccine in use, when the oral polio vaccine (OPV) is fully phased out. Yet IPV is substantially more expensive than IPV – up to 15 times per dose – and it is also harder to deliver, needing trained professionals to give the injection. In addition, global supply constraints stand in the way of the important task of ensuring that every child worldwide is receiving this vaccine.

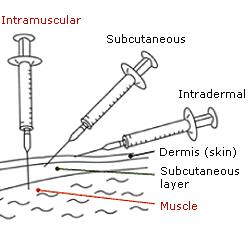

Building on a growing body of research that shows IPV can be given in fractional doses, the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on immunization (SAGE) recommended this October that countries consider using 1/5 of a dose delivered intradermally in both routine immunization schedules and vaccination campaigns. India and Sri Lanka have already adopted this methodology.

This innovative approach would reduce the cost of using IPV in the future, once OPV has been withdrawn from use. This is important: as even once eradication has been achieved, maintaining high immunity will be necessary for some years, in case of a circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreak or a containment breach of a virus from a vaccine manufacturer or laboratory.

But developments to ensure that every child can receive the benefits of being vaccinated against polio have not stopped at reducing cost.

Making it easier to reach every last child

Fractional doses of IPV need to be delivered intradermally into the top layer of the skin, rather than into the muscle. This requires different administration methods, training and tools to deliver it, although all other aspects of storage and handling are the same. Until now this has been done using the needle typically used to deliver the BCG vaccine, which is short and narrow, making it easier it get the vaccine between the skin layers. This can be a challenge for health care workers used to deliver IPV into the muscle.

But new delivery devices could simplify this work, reducing one of the barriers to administration of fractional dose IPV. This could greatly alleviate the global IPV supply constraint, by maximising all available vaccine supply and enabling more children to be reached with it.

Needle-free injectors

Following clinical trials, WHO has started stockpiling the Tropis needle-free injector, a device that can deliver the vaccine through a narrow, precise stream of fluid that penetrates the skin without the use of a needle, whilst still delivering a similar quality as the BCG needle.

Though health workers will still need special training, the use of these devices could make their lives much easier by making some of the huge advantages that applied to the oral polio vaccine available for IPV as well.

Micropatch needles

A second innovation could also potentially transform IPV delivery. Micropatch needles are also being researched, coming with the advantage that they could be delivered not only by healthcare professionals, but also by trained volunteers, like OPV. Each patch, about a square inch in size, contains 100 vaccine-filled needles each the diameter of a human hair. When pressed into the skin, the needles dissolve, leaving only the patch backing. This approach would also revolutionise GPEI’s ability to deliver IPV as quickly and easily as OPV. Being able to carry out house-to-house vaccination campaigns would be a game-changer, especially in areas where reaching every last child can be a challenge. WHO is looking forward to clinical studies to evaluate this new approach.

| The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) is highlighting the innovations that are helping to bring us closer to a polio-free world. Find out about other new approaches driving the polio eradication efforts by reading more in the Innovation Series. |